Salt Lake City Weekly- August 21, 2019

Swan Song

The magical 25-year journey of Swan Princess from box-office flop to beloved franchise.

By Scott Renshaw @scottrenshaw

There's not much mistaking Seldon Young when he walks into his Layton office for an interview. The smiling, round-faced man is decked out in a tuxedo-style suit patterned with pink-and-white diamonds, each one filled with characters or logos from 1994's The Swan Princess—an animated feature film, based on the same story as the beloved ballet Swan Lake about a princess under an enchantment. Before we begin, he encourages me to step out to the parking lot; outside the front door, there's an SUV with a similar checkerboard design. "It stands out," Young says with a laugh. "We get a lot of interesting looks, along with people doing some distracted driving."

Young has a savvy sense for marketing, but he's also selling a product he believes in with all his heart. You'd have to be that committed to still be hawking the same brand 25 years later, especially after the original Swan Princess flopped in theaters, leaving Young and his company millions of dollars in debt. Yet this month, the Swan Princess franchise released its ninth installment—The Swan Princess: Kingdom of Music—with a 10th film already in production and set for release in 2020. A gala anniversary celebration is planned in Los Angeles. How did a potential disaster become one of the longest-lived feature film franchises in history?

"I consider myself a turnaround artist," Young says. "And I consider this property the greatest turnaround of my career."

Once upon a time ...

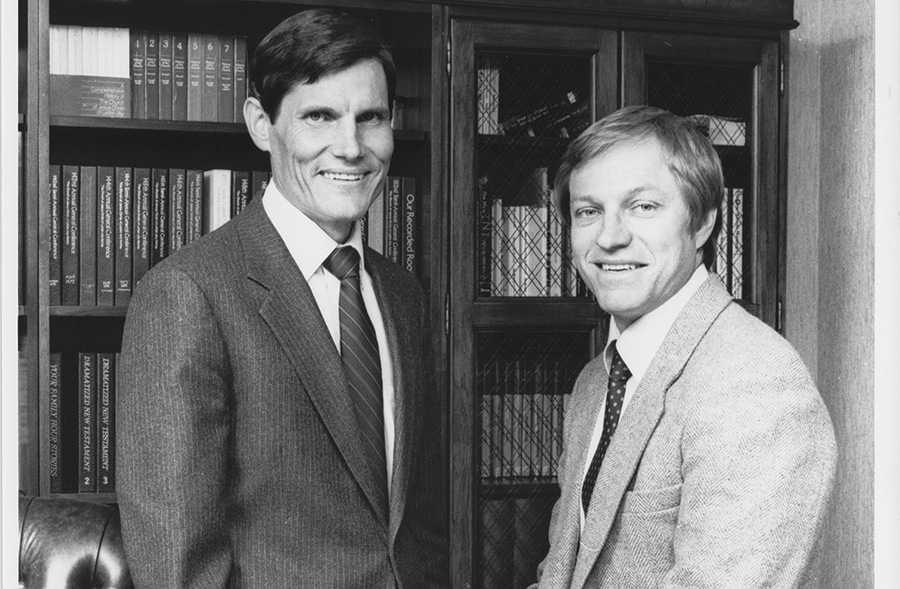

Young's path toward show business wasn't intentional, but instead more of a natural progression for a guy who describes himself as a "serial entrepreneur." Fresh out of college in the 1970s, he started selling illustrated books of scripture stories under his then-manager, Jared Brown. From there, the Utah-based company branched out into dramatized audio versions of biblical and historical stories, producing more than 500 30-minute installments. Taking the next step—into the nascent market of home video in the mid-1980s—came as a result of Brown's inspiration.

"Jared and I were on the road, staying in a double bedroom in a hotel, and he's sitting on the edge of the bed watching cartoons," Young recalls. "I was not heavy into cartoons, but he loved them [and] was just cackling. And he turned to me, real serious, and said, 'Do you know what? We need to turn all these stories into cartoons.' And that was the launch."

Young and Brown explored a variety of potential animation partners for their planned Living Scriptures series—including Hanna-Barbera, the company behind kiddie classics like Scooby-Doo and The Flintstones—before they became aware through composer Lex de Azevedo of a director named Richard (Rick) Rich, a Utah native, who was just leaving The Walt Disney Co. after having co-directed features like The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron, in addition to Winnie the Pooh and Mickey Mouse shorts.

"Disney was at this point starting to change to digital animation, just barely," Young says. "They weren't doing as much ink and paint. That gave us the opportunity, because there was a whole flood of people available [from Disney] to start doing our own stories."

"When I was trying to start my own studio," Rich recalls, "I wasn't thinking of doing my own feature to start with. What was interesting then was the Living Scriptures fell right into that. They were featurettes. I knew that format really well."

The half-hour Living Scriptures featurettes were a success, but the idea of a feature film began to percolate. "As we were producing these, every time we would go to the studio, they were pitching us with storyboards this story of Swan Lake, the ballet," Young says. "Rick had been working on this idea for some time and hadn't figured out how to solve some of the problems with the story, but he was looking for someone to help him finance it."

Rich recalls, "I wanted to do a fairy tale that would have equal impact as Cinderella. That was my burning desire. Fairy tales just last, they don't go out of style. I wasn't keen on contemporary stuff—that passes.

"I always thought that Seldon or Jared thought, 'If we didn't do [Swan Princess], we could lose them.'"

There was a beautiful princess ...

Work began on The Swan Princess, including developing storyboard treatments and folding Rich's animation studio under the Nest Family Entertainment umbrella. But Young admits that he was not keen on the project at the outset from a business standpoint. "To me, you finish and do what you're best at," he says. "We were good at direct sales. We had built tremendously emotional stories that had great music behind them. We didn't know anything about the movie business. Zero."

Swan Princess had an initial budget of $12 million, most of the funding coming directly from Brown and Young's own pockets. Soon, Young realized that it would be necessary to raise outside financing to complete the project, something else Young had no prior experience in. Yet ironically, he says, it was thanks to the ongoing process of selling the idea of The Swan Princess to others that he ultimately sold it to himself. "Once you're fully engaged, your passion kicks up," he says. "You hear that story [you're telling] over and over again, and you think, 'You know what? This could be a really cool story.' You're blinded by everything. But those blinders really help, because you have such confidence convincing people to put up money, allowing us to go forward."

Meanwhile, on the production side, Disney alum Rich was putting together a voice cast that included veterans like Sandy Duncan, John Cleese and freshly minted Oscar-winner Jack Palance. Finding his Princess Odette, however, was proving to be a challenge, despite traveling to New York to audition Broadway performers. "What I was trying to find was a voice that had the sound of a princess voice, innate in the voice itself," he says. He finally found it in Michelle Nicastro. "She was Odette in every way, shape and form."

- Nest Family Entertainment

Young continued raising money, while discovering that there would be expenses beyond simply completing the film. They found a willing distributor in New Line Cinema, but the company was involved only in booking the film into theaters, not with providing any financing. Eventually, the independent producers raised the funds required for prints and advertising in addition to production costs—a total of some $45 million.

The Swan Princess team was optimistic, however, that they could find theatrical success, even as Disney had begun the resurgence in its animated features like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast and Aladdin. There was even a model for independent animated features overseen by an ex-Disney employee: Don Bluth, creator of the An American Tail and Land Before Time films. "What it did to us is, 'If they did that good, we should do that good,'" Young says. "American Taildid good, we should be able to do that kind of thing. We thought everything would fall into our hands. That's what happens to you. There's not wisdom, and some of the people we were hiring didn't give us some of the wisdom we should have had."

Who was threatened by a villain ...

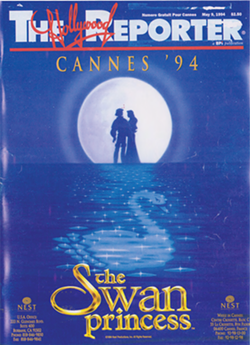

New Line prepared to release The Swan Princess into theaters on Nov. 18, 1994—a family film primed for the holiday movie season. But as the date neared, a massive threat appeared. Disney's blockbuster The Lion King had been pulled from theaters after Labor Day, and the company scheduled a re-release—on Nov. 18, 1994. In its review of The Swan Princess from November 1994, Variety bluntly referred to Disney's decision to release on the same date as "sabotage."

Young, for his part, is more politic about Disney's actions from a 25-year remove. "At the time, yes, we were really upset," he says. "We saw all kinds of things that were sabotage in nature. Now I say, 'Look, Disney does their job,' and I have to navigate around that and not hold feelings about that."

When they learned of the Lion King plan, Young says, they had some people recommending that they postpone the release until the following spring. "But everyone knew we had huge product tie-ins out in the marketplace [for Christmas], 95 licensees," he says. "I would have had every one of those companies suing my butt off. I had no choice—I was blocked."

- Courtesy Nest Family Entertainment

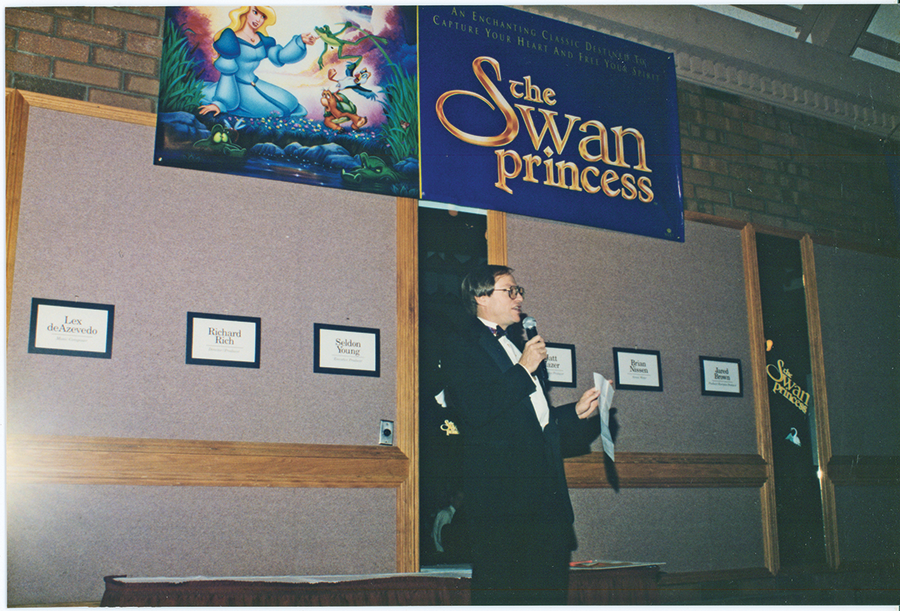

- Seldon Young at the 1994 premiere of The Swan Princess.

Still, it became immediately obvious to Young during that opening weekend that The Lion Kingwas going to eat The Swan Princess alive. And it did, in fact, outstrip Swan Princess's weekend take by a 2-1 margin. He knew the trouble they were facing when he went to a Layton theater on opening night, and observed the dynamic as families would walk up to the box office to decide what to see. "You'd have four girls and one boy in the family, and they're looking at these choices and the girls are going, 'I want to go to Swan Princess,' and the one boy is saying, 'No way, I'm not going,'" he says. "And they would go to Lion King. You knew as you were going around to theaters, we're going to get crushed."

"We were getting hourly reports," Rich adds, "and we knew we were getting crushed. And I was devastated. I can remember lying in bed with my wife, and she turned over and said, 'Rick, you have to realize you made a great film.' That changed everything for me. I knew I'd made a good film. I made a film that should not have failed."

Nevertheless, the production was facing a loss of somewhere in the neighborhood of $18 million, and the various advances and other financing deals that Young had made seemed to make it unlikely that the film would ever be in the black. There was enormous disappointment, and some depression, in the sense of, 'How do we overcome this?'" Young says. "We got fortunate to be the No. 1 selling video for a week or two when it was first released, but all that does is pay off some of the people that put up advances for us. Swan Princess got buried in debt. One of the deals with Sony, was, 'We'll give you an advance if we can have international marketplace.' Because Sony had that, they technically had control of my film, even though we owned the IP [intellectual property]. So, how do you get that out of jail? And that's part of the fun of the story."

Then a hope appeared ...

Young, Rich and the rest of the Nest team had retreated to their core Living Scriptures business in the wake of The Swan Princess' theatrical flop, when they received a call from Sony's Columbia-TriStar Home Video division, which was handling the film in overseas markets. The video was selling well, to the extent that the Columbia-TriStar CEO had described it as "energizing our international team." Would Nest consider producing a Swan Princess 2?

"I said, 'OK, we're going to have to act fast. If we have animators leaving, we're going to have a hard time,'" Young says. They quickly put together a contract, with Sony once again handling international distribution and Warner Home Video handling domestic. "Now I'm in a little bit of a different game," Young says. "They pay for the film, I get producer fees out of it. So we get something for it. ... And as we were finishing [the second film], this is where you get real bold: You ask again. And they said, 'Why not? We love Swan Princess, we've made a lot of money on Swan Princess.' So we did Swan Princess 3"

The Swan Princess: Escape from Castle Mountain was released direct to video in July 1997, with The Swan Princess: The Mystery of the Enchanted Treasure following in August 1998. The videos continued to make money for Sony, as Young would see on balance sheets over the years. But Nest still owed advance money to Sony. It required a bold move more than a decade after the release of the third film for the franchise to have a chance at another life.

- Courtesy Nest Family Entertainment

- Jared Brown, left, and Seldon Young in the 1980s.